|

|

|

One of the most pleasurable

and overwhelming experiences for foreigners coming to Central Asia is

the incredible hospitality and honour bestowed upon guests in this part

of the world. This is particularly contrasted with the unflinching rudeness

and lack of service to be found in many of the Intourist hotels, where

bolshy middle-aged women greet even the most earnest request with withering

indifference.

|

|

Do not assume that Uzbek hotels reflect

true Uzbek hospitality as many of them seem to have drawn from Intourist

traditions rather than their own culture. Hospitality plays a pivotal

role in Uzbek culture. Long term business contacts, arrangement of marriages

etc. all take place around large plates of plov. There is an Uzbek proverb

stating that a guest is more honoured than your father. All guests visiting

a home should be fed, even if their visit is just for two minutes. If

you drop by to pass on news to a neighbour or to borrow something, bread

will be brought to you and you should break off a token amount in order

not to violate the laws of hospitality. To leave unfed would be a shameful

thing.

If you do have the opportunity to visit a local home

in Khiva, it’s worth knowing a little about the expected etiquette. Firstly,

a gift of flowers or chocolate or something from your own country is always

worth bringing. Whilst your gift may be refused initially, you can always

offer it to the children of the house. Be assured that protests of refusal

are not heartfelt. However, if you do bring gifts, do not expect visual

displays of pleasure or gratitude, as this is usually considered inappropriate.

‘Women greet other women by embracing and sometimes kissing’ |

‘In village homes, hand washing may also be done outside’ |

On entering the house you will be greeted by your host. Men should shake hands with men and possibly embrace, whilst women embrace and may also kiss. Your host will then wait for you to remove your shoes and will lead you to a basin of water for you to wash your hands. It’s very important after washing your hands not to flick the water off them, as this is considered most impolite, (and may stem from Mongol traditions of venerating water). If you are not offered water, this may come once you’re seated in the form of a small jug and basin.

‘Poorer families generously offer what they have....’ |

You will then be led into the guest room to sit on corpuches, (cotton mattresses) around a low table or table cloth spread on the floor (known as a Desterkhan). You will be ushered to your places. The seat of honour is the place furthest from the door with your back to a wall and this place goes to the oldest male guest. Once seated, your host might say an opening prayer, however the main grace is said at the end of the meal. |

‘... Whilst the wealthy entertain lavishly’ |

‘Whilst in Urgench many people buy bread, in khiva most families bake their own.’ |

The Desterkhan will be covered (literally) with plates of salad, cakes, sweets, bowls of fruit and rounds of Uzbek bread, bottles of soft drinks. Vodka and teapots of green tea. Feel free to help yourselves to all of this. However, make sure you don’t get full on the appetizers, as the main course is still to come. Your host will take one of the rounds of bread and tear it up, giving pieces to all the guests. Bread is considered holy and you should treat it with respect. Don’t put it face down on the table and don’t waste it. Your host may then offer you tea in a small cassa (bowl). This is often poured in and out of the teapot three times to strengthen it. If you are given a small amount, don’t feel offended; your host has only given you a little so that he will have many opportunities to refill your cassa as the meal progresses. In Tashkent and other parts of the country, the host will constantly badger you to eat and drink up. However, in Khorezm hospitality is refreshingly laid back with the host saying ‘Oling oling’ (‘Take, take!’) only once or twice.

‘Green tea being served. Often it is poured back into the pot three times in order to strengthen it’ |

The women of the family will probably be absent preparing the food and the entertaining will be left to the men of the family. There is an Uzbek saying that a guest is greater than your father and as such your host will also play the role of servant. Be a good guest and allow your host to serve you; this is not a culture where offers to help with the washing up will be understood or appreciated.

‘Your host will only be satisfied when you’ve eaten a huge ammount of food’ |

|

|

After grazing on the appetizers, the

main dish will be brought in. This is usually Uzbek pilaf known as plov,

but may be a different dish. Plov is normally served in mountainous portions

on a large plate that is shared between two or three people. On top of

the carrot and rice pile, your host will place lumps of meat and maybe

half a garlic. You may be provided with a spoon; however, plov is best

eaten with your right hand. Your host will happily show you how and your

attempts will provide entertainment for the whole family. You will be

urged to eat and keep eating and it’s important that you make a significant

dent in your plov mountain. However, you don’t have to finish everything,

and as long as you express appreciation for the food, your host should

be happy.

At some point during the meal, your host will start to open the ubiquitous

bottle of vodka. Toasting with vodka may be a tradition imported from

Russia, but has become entrenched in Uzbek culture. Uzbek men can happily

polish off a whole bottle of vodka and still go to work the next day.

They are also very good at pressuring others to drink with them. If you

would prefer not to drink then politely but insistently refuse. The best

way of refusal is to pour yourself a cup of tea or soft drink and initiate

a toast. As long as you respect the toasting tradition, your absence of

vodka should be overlooked. If your host coaxes you with ‘just 100 grams’,

remember that there is no such thing as 100 grams, just the first glass

of many.

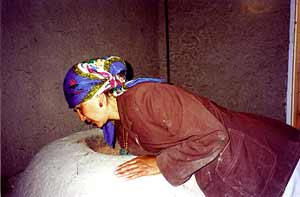

‘Your host can show you how bread is made in a tunda oven.’ |

|

You may be wondering when the visit will come to an end and what your cue is to leave. Once the main course has been eaten, your host will finish the meal with a large plate of melon (if in season). Once this is finished you can start asking your host for permission to leave. Your host will probably refuse the first time urging you to stay longer and possibly offering you a bed for the night. After another five or ten minutes, you can start explaining how late it is or some other excuse and ask the eldest male to say the closing ‘Amin’. All present will then cup their hands as the eldest male prays. However inebriated the company might be, this tradition is always observed and signals the end of the meal. You can then proceed to leave. Your host may well take a round of bread from the Desterkhan and pile it with sweets and cakes and then fold it over and hand it to you or stuff it in your bag. You will then be seen to the door or even half way down the street, with your host insisting that you come back and visit again.